Photo Source: Wikipedia

Money is a language, a way of expressing value to carry out exchanges of goods and services between human beings. It is a belief, a technology developed to be able to exchange and store value over time.

Contrary to what many might think, current traditional currencies like the US dollar, Japanese yen or British pound are all fairly recent. In fact, they are all a type of fiduciary money (also known as “fiat“).

Officially born in 1971, modern money is not backed by gold or anything else, it is simply paper or figures on a computer. The “backing system” is, quite literally, people’s trust and faith in any given country’s economy and the stability of their government and financial system.

Surprisingly, this simple notion is still far from common knowledge: people all over the world are unconsciously accepting money to have value despite the absence of intrinsic value.

This is one of the biggest issues: basic education programs (and even advanced ones!) don’t teach that money is a support system that evolves and adapts to service an ever changing human society; instead we are all led to believe that we are born with a type of money that has always existed as we have it today.

The Origins of Money

The origins of money are as old as the history of mankind itself, and the earliest human economic exchanges are far from the present reality. Money has been through countless iterations throughout history, from barter, to the appearance of the first currencies, to the arrival of today’s fiat currency to Bitcoin and digital currencies. Undoubtedly, a whole path full of progress and great technological evolutionary leaps, always intertwined with the evolution of humankind, societies and economic systems: every economical innovation and shift of power produced a new form of money.

Early Exchange Mechanisms

The earliest forms of money go back thousands of years: living in permanent settlement in an organised society, brought with it the division of labor and specialisation; effectively making people not self-sufficient, thus creating the need to obtain things that others had in exchange for the product of their own labor. A farmer could trade in units of his crop for medicinal herbs, pottery or tools created by someone else. This led humans to create different types of exchange mechanisms.

In ancient times, bartering did not even exist: material goods had no exchange value, but at most could be a “collective gift” within religious ceremonies, festivals and banquets.

In short, profit and gain did not exist. Even when collective gifting shifted to bartering, the concept remained that of equal exchange, which drew inspiration from religious rituals.

Barter, the first form of money

So then came the barter economy, a system of economic exchange in which units of goods, products and services are offered in exchange for others.

This is a simple way to exchange value and one of the most basic forms of money.

It is also the furthest to what we know and use regularly today, as well as the most complicated to apply as clearly inefficient in settling mondane transactions required in everyday life.

There are indications that barter dates back to the Palaeolithic period, that is, around 15,000 B.C., and according to Investopedia barter really made its mark in Mesopotamian tribes and then subsequently adopted by Phoenicians before spreading further.

The idea of exchanging a product such as salt for copper, or cloths for grain, was theoretically simple when barter appeared for the first time to regulate human transactions. In reality, this kind of exchange is difficult to execute and very often quite an unfair system. Too often there were differences in power status between the parties, or the goods being exchanged were complex to store, transport and negotiate. All this makes barter a very inefficient and unfair form of exchange.

As you can imagine, this unfairness very often became the “casus belli” (cause of war) between opposed tribes and nations. Given that resources and generally goods were not distributed equally to different groups of humans, the barter wasn’t a scalable exchange system that could endure the test of time.

Although less used than in the past, barter is still in use today as a means of exchange: Venezuela, Argentina, or Zimbabwe are examples but also in developed countries. What it tells us, that despite being the oldest form of money, its use is still ingrained in human’s DNA as a natural form of exchange.

Exploring alternatives to barter

Other money forms of money such as spices and flavourings, perceived as valuable at the time, were experimented as a yardstick and system of exchange. Consider that in ancient Rome salaries (from the word ‘sal’, salt) were handed out in exchange for labor. Spices remained an important part of ancient commerce for centuries particularly in Middle Eastern, North Africa and Asian societies where such commodities became a proxy for wealth and used in all sorts of applications from flavouring food, making perfume, embalming the dead or important ingredients in traditional medicine.

The first attempt to solve the inefficiency of barter and a major leap in the evolution of money, was the arrival of minted coins: physical means of exchange, generally made of precious metals.

The arrival of coins, the first monetary revolution

The difficulty of bartering for exchanges of small value began to involve human inventiveness. As a result, the first coins began to be minted: around 600 B.C., in three places on the planet independently, Lydia (Asia Minor), China and India. The metal was cut into small portions and marked with an identifying mark, creating the coin with the specific function of serving as currency, a new system of exchange.

Later, with the conquest of Lydia by the Persians, the expansion of coins around the world began to grow. People such as the Greeks, Romans, and Chinese served as an epicenter for their neighbours, and populations under their rule used their coins as a system of exchange.

These early coins were generally made of precious metals. The Lydians minted their coins in gold and silver, weighing between about 4 grams and 60 grams. This all depended on the quality of the material, alloy, and size of the minted coin.

The expansion of currencies around the world

Currencies quickly became a highly desired medium of exchange. These greatly simplified the buying process and set aside some of the injustices that barter had, mostly because the value of the coin was in its coinage and the value of a material whose labor was difficult to perform.

On the other hand, the appearance of coins also made it possible to create the first anchor patterns as standard units of measure. A gold coin could be used by a king to order the minting of a certain amount of copper or even wooden coins. Thus was born the concept that we could protect value and use other representations of money to mobilise value.

Roman coins marked the evolutionary point of coins that would later be used by the people of these regions to this day. They contributed not only to the development of trade but were an innovative tool in the field of propaganda: each coin bore a message by means of an effigy, usually of the emperor, and a scene recounting a political event, a glorious military achievement, or a religious celebration. This concept is still valid today with modern money: coins and banknotes have inscriptions, pictures or images of great leaders of the recent past of a nation or references to a specific culture.

In 23 B.C., the great Emperor Augustus was the first to reform the Roman Empire’s monetary system, which saw the emperor having total control over the issuance of gold and silver coins for state expenditures: leaving at the senate control over the minting of bronze coins, usually handled by the people.

Emperor Augustus gave birth to the first money centralisation project on such large-scale.

With coins, a new important concept arises: the “pegging” system.

While it was pretty self evident with gold and silver, other types of metal, such as copper or even alloy, started to become extremely popular with the general population.

Only senators and wealthy nobles had access to gold or silver coins; most people had to rely on less valuable metals to carry out their daily transactions, for instance using copper.

Although an improvement compared to the barter, the coinage system main issue was that given the value of each coin is given by the very material of which it was made, there were great limitations to usability and exchangeability; making it not a broad solution for all types of transactions: from buying bread at the local market to buying a piece of land.

The origin of today’s money

Although the concept of banking goes back to Mesopotamian times, where loans were first issued for interest, it was mainly in the Middle Ages where they played a key role in the evolution of money with the emergence of paper money in Europe.

Although it is true that paper money can be first attributed to China in the 7th century, with the voyage of the Venetian Marco Polo in the 13th century this instrument began to be known outside of China.

It would take centuries to actually be used across Europe. In the modern sense, banking had its beginnings in the wealthy cities of northern Italy, such as Florence, Venice, and Genoa, in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance.

Florentine bankers like the Bardi and Peruzzi became very wealthy and powerful; but none like the De Medici family, who dominated banking in 14th-century Florence and established branches in many other parts of Europe.

The birth of Banking

The myth of “money in the bank” was born in Florence under the De Medici family ruling, where their banking business raised so much in popularity thanks to 4 major innovations:

- Double-entry bookkeeping: accounting technique recording a debit and credit for each financial transaction and providing a complete record of all financial transactions for a business.

- Letter of credit: providing an economic guarantee from a creditworthy bank to an exporter of goods.

- Branch banking: the Medicis created bank branches across all major European cities to support their customers’ commercial and financial activities, providing them with the same banking service.

Holding company: By creating the branch network, the Medicis also pioneered the holding company structure. The Medicis set up each branch as a partnership and the Medicis were the majority shareholders.

If you were a merchant in need of trading (buy prime material such as metal, sell finite products like tools and utensils) all around Europe in the 13-14th Century, your main issue was that you needed to travel with a large amount of physical money, usually in the form of gold, silver or similar, making you an easy target for all ill-intentioned people. This is precisely where the De Medici banks came in: they provided a letter of credit issued in the holders name, under the authority of the nearest De Medici bank that was equally valid in any other De Medici branch throughout Europe. The letters of credit changed commerce dramatically, making the trader trips incredibly safer, as such letters were only “bankable” if the holders themselves were to present it to a bank to make a payment.

This single feature made the De Medici business so popular that most trades were regulated in “Fiorini” (the Florentine currency) and even without a physical exchange of money: using their advanced accounting system, if all the parties involved within a transaction were clients of the De Medici banking business, then the transfer would be settled internally.

Thanks to those innovations, people’s lives changed irrevocably: everyone trusted the De Medici bank to the point that it became popular to say that if an event was certain that it was as “deposit money (Fiorini) into a De Medici bank account”.

As we can see, TRUST became the dominant factor here: coins were intrinsically valuable but weren’t a reliable method of settling commercial and financial activities on long distances or complex transactions. The banking system solved this problem by introducing trust in the equation, relying on the issuer of a paper note rather than the value of the amount of precious metal carried in the form of coins by each person.

Ultimately, these innovations led to our current perception of money.

Introducing the banknotes and central banking

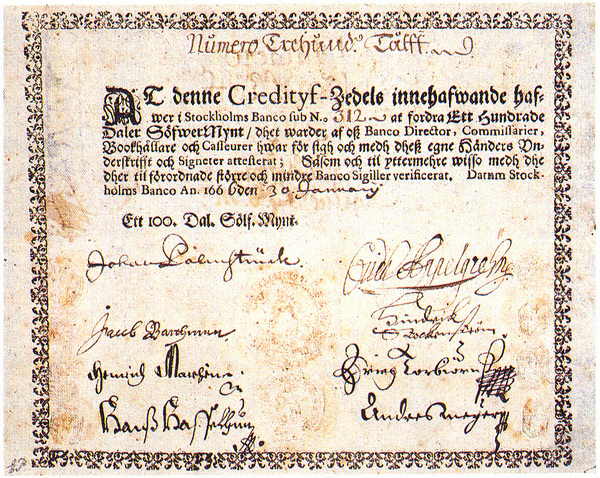

The first banknotes of which there is evidence appeared in Sweden in the year 1661 , at the hands of money-changer Johan Palmstruch, who issued them as a “receipt” for those who deposited gold or other precious metals in the Bank of Stockholm, which he founded.

This is where gold-backed paper money was born. That is, people’s gold coins, which were heavy and difficult to part with, were stored in highly protected safes in exchange for documents that stated something like: “This paper is equivalent to so much gold in Bank X.” The same applied to other metals such as silver and copper.

As this practice took off, bankers started realising that few people came to claim back the gold as they grew comfortable trusting the bankers and holding onto the paper notes. Given this situation, bankers saw the opportunity to start lending the idle gold sitting in their vaults to other people, receiving interest on those loans. It is at this point that banks effectively started expanding the supply of currency through fractional reserve banking i.e. issuing more money than actually the physical money secured in their vaults.

All was running smoothly until 1660 King Charles X Gustav died and the government decided to mint new copper ingots of lower purity. Depositors flocked to collect their copper ingots of the highest purity (also called Gresham’s law, whereby when two are coins in circulation, people keep the good one and use the bad one), but because Palmstruch had lent them out, there were not enough. Therefore, in 1661 the ingenious Palmstruch decided to decouple the issuance of “banknotes’ ‘ with deposits so that the sole guarantor of the banknotes was the bank itself. These banknotes were the Kreditivsedlar and secretly represent the birth of fiat money, which is backed only by faith or trust.

It seems that Palmstruch had succeeded in his endeavour, but he did not count on this money generating a new phenomenon in Sweden: inflation. After a turbulent period of economic crisis, in 1667 the bank went bankrupt, failing to honour commitments derived from the Kreditivsedlar. Palmstruch was initially sentenced to death, although he was later pardoned and went to prison.

But in 1668, having sensed the power of banking, the Swedish parliament decided to establish the first central bank in history: the Swedish State Bank, with exclusive rights to issue banknotes. Only 26 years later, in 1694, the Bank of England was created, the central bank that has served as a model for most of the world’s central banks.

That is the story of how paper money creation was privatised and institutionalised in governments, taking away the ability of any other party to control money. Only a country’s central bank would have the ability to issue valid money, truly caring that there was gold backing the bills.

But even central banks could not bear that promise for long.

Fiat money, uncontrolled issuance and loss of purchasing power

The arrival of the Bretton Woods agreements in 1944 changed everything. From then on, fiat money became the new standard of money. Money with no value of its own, but which has legal value. These actions, which should have led to a higher level of wealth for all, eventually led to the emergence of serious economic imbalances around the world.

The central banks of many nations began to issue currency at their own discretion, triggering the first problems of aggravated devaluation of purchasing power of such currencies. Even the dollar itself, the standard currency, faced this reality. To the point where the purchasing power of $100 in 1956 would be the equivalent of $956 today.

In 1971 the President of the United States Richard Nixon faced a historical impasse. Against the backdrop of the Vietnam war which put the US at the brink of bankruptcy, President Nixon was facing the pressure of increasing inflation on one side and foreign governments increasingly seeking to redeem their dollar reserves back into gold on the other. This combination of circumstances led to the famous “Nixon shock”: a series of economic measures and the unilateral cancellation of the direct international convertibility of the United States dollar to gold.

Although Nixon’s actions did not formally abolish the existing Bretton Woods system of international financial exchange, the suspension of one of its key components effectively rendered the Bretton Woods system inoperative. By 1973, the current regime based on freely floating fiat currencies de facto replaced the Bretton Woods system for other global currencies.

Although there are those who think that euros or dollars are backed by gold, this is not the case. Money as we know it today is not backed by anything, being issued by the local central bank, which from its position of power determines that this is the money people should use.

The power of creating fiat money, whose value is not tied to anything tangible but only to a political promise of never ending growth was broken time and again, is the main cause of some of the greatest economic and financial disasters in history.

The ability for countries to print as much money as they want leads to unrealistic economic planning, often driving corruption and mindless spending which citizens ultimately pay for through taxation. In the end, that money-printing machine safely generates only one thing: economic chaos.

This problem along with other unhealthy practices in economics are what led us to economic crises like 2008. Faced with this reality, the need for a new kind of money, not controlled by governments and central banks, triggered a groundbreaking idea leveraging technology, mathematics, and computer science.

The birth of Bitcoin, a decentralised, open and secure currency

The birth of Bitcoin on January 3, 2009 represents the latest step in the evolution of money. According to the original Bitcoin whitepaper: “[Bitcoin is] a purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash that would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution”.

We have always seen money as something physical, tangible, but Bitcoin has changed this paradigm. Although we have had digital money for a long time (in our bank accounts or systems like Visa and PayPal) the truth is that these systems were just another representation of the prevailing fiat money system of trust and fractional reserve banking introduced by the Medicis and then evolved through central banking over the past centuries.

Bitcoin promises something totally new. A system whose value is given by the work done to generate and operate it, as well as the trust and supply and demand dynamics that its users impose. In other words, there are no central banks here, no government to control them. Bitcoin is autonomous in every way.

To know more about Bitcoin, check out our next article.